The unofficial official ideology of British institutions

A joint project by the BBC and the Royal Society exposes the establishment's ideological underbelly. And it is a grotesque thing.

Two of the most important (or perhaps more accurately ‘self-important’) British institutions are the Royal Society and the BBC. To those that may not be from these shores, and not be familiar with them, the Royal Society is the world’s oldest science academy, once chaired by Isaac Newton himself, and the BBC is the world’s oldest state broadcaster.

The former institution was founded at the birth of the Age of Reason, during which time the divine right of the ancien régimes began to falter and fade, in bloody messes. Accordingly, and in the wake of extreme political turbulence, just two years into the Restoration of the monarchy, with the blessing of the new King, Charles II, the Royal Society adopted the motto, nullius in verba — on the word of no one. Scientific authority did not rest on gods and monsters, princes or priests, but on the new knowledge.

The BBC was similarly established, by Royal charter, in 1927. The 267 years that had passed since the establishment of the Royal Society had seen such scientific and economic developments that it was now possible to transmit sound wirelessly into radio receivers in people’s homes. According to the Charter, more than two million households had applied for licences — a reflection of Britain’s paternalistic and authoritarian baseline — allowing them to install and operate ‘apparatus for wireless telegraphy’ such was the appetite for this new technology. But this created a new problem, hinted at by the Charter’s following paragraph…

… Whereas in view of he widespread interest which is thereby shown to be taken by Our People in the Broadcasting Services and of the great value of the Service as a means of education and entertainment, We deem it desirable that the Service should be develop and exploited to the best advantage and in the national interest…

From the outset, the British Broadcasting Corporation was a vehicle for propaganda. If not the state’s propaganda as such, the establishment’s propaganda would be piped into Britain’s homes, and the BBC’s monopoly on broadcasting, and therefore culture, values, and ideology, would be sustained for decades — a century, in fact — by the licence fee payable by anyone who had the means to receive the transmissions.

So what is this historical preamble about? As I have pointed out many times before elsewhere, the predominance of climate change in an institution’s machinations appears to evidence that institution’s degeneration from its traditional or founding purpose or function — its existential crises. And anyone who claims that the institutions of the British establishment — from the scientific academy to the state broadcaster, and the monarchy that established them — are not in crisis, has been living in a cave for the last thirty or more years.

Earlier this week, the Royal Society published this video on its X feed.

https://twitter.com/royalsociety/status/1764191730126254172

The ongoing and unfortunate X-vs-Substack squabble prevents the tweet being embedded properly here. I believed that the video was new. But it was apparently made in late 2022. Nonetheless, it is still worthy of comment, despite the fact that it has had relatively little audience engagement (just 10,000 views and 92 ‘likes’ on Youtube, and similarly disappointing results on the BBC’s website and the Royal Society’s tweet). The film is a jumbled mess of factoids and ideology that speaks to the depth of the crisis that both institutions are suffering, which must be seen to be believed, so please watch it before reading the rest of this article. On the word of no one, is the motto, after all — don’t take my word for it.

It was the Royal Society’s claim that ‘the destruction of nature is the backbone of the economy’ which caught my eye.

It is such a categorically ideological statement, and one which has no foundation in science. Even taking for granted the conception of ‘nature’, the notion that the economy depends on its destruction also lacks any historical perspective.

It is a claim that continues throughout the video, and is advanced by Dr. Sharad Lele, who appears to be a Senior Research Fellow at the manifestly agenda-ridden Foundation for Renewable Energy & Environment. Lele claims:

The root causes of the loss of wild nature are complex, But what is driving the biggest changes today is capitalism.

The Royal Society was established approximately a century into what historians call the modern era, and about the same distance past the birth of capitalism as such. But as we point out over at Climate Debate UK:

In Britain, for example, the mid 1500s to the mid 1600s was the century of peak deforestation, in which Britain ‘ran out of wood’ and the switch to coal began. Historians suggest that deforestation began in the British Isles during the Neolithic era, around 4000 BC, and that by the arrival of the Romans through to 1086 (as recorded in the Doomsday Book), England’s wooded areas occupied just 15 percent of the land. According to the UK government’s environmental accounts, 10 percent of England and 13% of the UK is now woodland – an afforestation that has seen a doubling of woodland area over the last century.

That is to say that by far most of the deforestation that happened on these isles occurred long before capitalism’s early steps. There was little prior to the Royal Society obtaining its charter that would qualify as an ‘economy’ in the way we understand it today — i.e. capitalist. If there was an economy, it was feudal, which is to say ‘pre-capitalist’, and organised much more around actual relationships between people, rather than around the trade of commodities as such. It was in large part the friction between the old and new that caused the violent politics of the era, on the continent and in England, and of course required the new settlements, which in Britain began to make a distinction between the right to rule and the right to make money, and between truth and power.

Moreover, this claim that the economy, and capitalism in particular, requires the ‘destruction of nature’ can be debunked at a much broader level of analysis than seventeenth century Britain.

Peak agricultural land use occurred in 1100. For 6,600 years, agricultural land area per capita exceeded 1.5 ha. Then, through the birth and into the era of capitalism the fall from its peak continued for centuries.

Thus, and very, very clearly, if the primary measure of mankind’s ‘footprint’ on ‘nature’ is the extent of agriculture, then the Royal Society’s anticapitalism is false in two respects. The destruction of nature is NOT ‘the backbone of the economy’ and capitalism is NOT driving the biggest changes today.

The Royal Society’s mythology imagines a time, when ecological foot prints were minimal, which simply never existed.

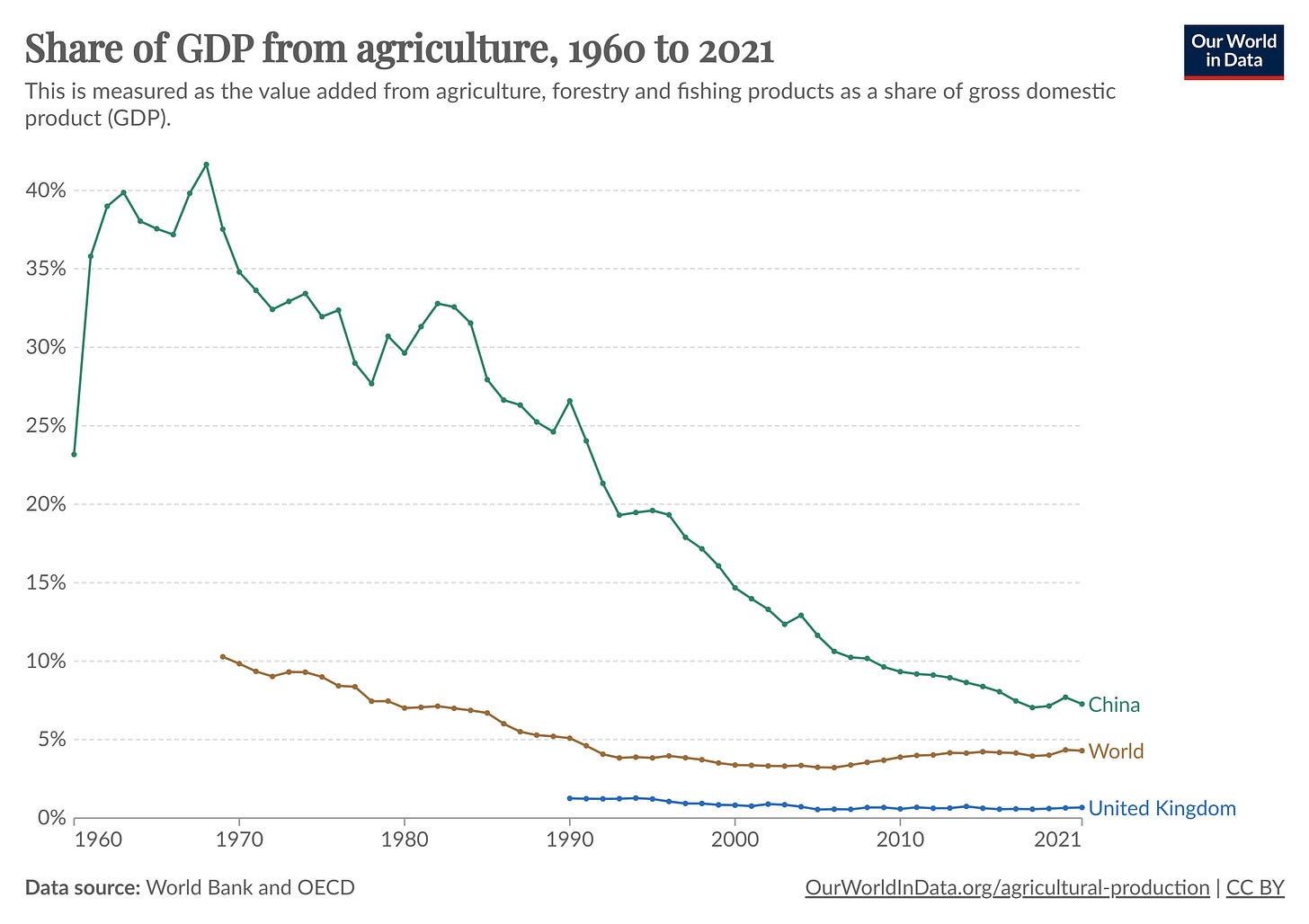

It is of course true that the world’s population has increased dramatically, and that did increase the footprint of agriculture, despite its per capita falls. But much of the world did not properly enter capitalism as such — as the Royal Society’s eco-communists mean it — until relatively recently.

However, recent decades have seen increasing liberalisation, and expanded access to markets. Consequently, agricultural production has increased while the land area has decreased.

Like it or not, Comrade FRS, that is capitalism. Moreover, agriculture represents a diminishing part of the economy. Liberalisation, much more than simple scientific and technological developments, produced efficiencies.

Finickity greens might object at this point that agricultural footprint is not the only measure of mankind’s wanton, profit-seeking destruction of nature.

But as the story of Britain’s deforestation and afforestation shows, coal saved the trees, and unleashed industrial potential — thanks in large part to the new political settlements that coincided with the establishment of the Royal Society, and the work of is past fellows. Others have pointed out, in the same way, that oil and gas saved the whales.

But let’s cut to the chase… These people are not scientists. They are not even idiot savants. They are dangerous ideological lunatics…

PAM MCELWEE: One of the big arguments is that it doesn't recognise the intrinsic relationships that people have with nature. We get senses of identity, sense of place, cultural relationships and rituals. And none of those can be properly represented with monetary valuation.

SHARAD LELE: We cannot depend upon pricing of nature as the solution to problems, because we cannot price the priceless.

PAM MCELWEE: I mean, the danger with putting a price on nature is that you create incentives for people to cheapen nature, because they want to make money off of it.

SHARAD LELE: Communities that live close to nature, and are dependent on nature directly, are often the poorest. As a consequence, given their low incomes, the economic value of what they get from nature, the positive benefits that they get, turns out to be very low. We do not want to price out those who have very low incomes, living close to nature, but in poverty, and therefore eliminating their voices from the decision-making system.

Lele even says it himself: “Communities that live close to nature, and are dependent on nature directly, are often the poorest”. How is it that the obvious fact that life in proximity to, and dependence on nature is the very definition of poverty, is within his reach, nonetheless so very far from him?

Associate professor of human ecology at Rutgers University, Pam McElewee is even more degenerate. She is concerned that the economic valorisation of ‘nature’ omits ‘intrinsic relationships that people have with nature’ — identity, culture, rites and sense of self…

What is this?!! Some eco-leftoid blut und boden?

People may well have ‘relationships with nature’. But the claim that they are ‘intrinsic’ is a claim that culture and identity are, as seeds and spores, not expressions of humanity. It is a weird environmental determinism. If there is a problem with the valorisation of ‘nature’ — and there are many — she has not identified it. And worse, in entertaining either notion, the Royal Society demonstrates the irrational mysticism that is hiding in full view behind scientific authority.

The idea that capitalism can save the planet is not new. In fact, the idea has a long history, and the Royal Society’s recent regurgitating of it is merely the latest neomalthusian burp.

The definitive text of its kind in the current era is Garret Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons, published in 1968.

Hardin argued that in order to save nature from over-exploitation, it must be wholly privatised. From the ocean floor, past the treetops, to the roof of the atmosphere, it must be sold to the highest bidder. Even human fertility must be regulated, he argued. And damn the consequences…

Is this system perfectly just? As a genetically trained biologist I deny that it is. It seems to me that, if there are to be differences in individual inheritance, legal possession should be perfectly correlated with biological inheritance-that those who are biologically more fit to be the custodians of property and power should legally inherit more. But genetic recombination continually makes a mockery of the doctrine of "like father, like son" implicit in our laws of legal inheritance. An idiot can inherit millions, and a trust fund can keep his estate intact. We must admit that our legal system of private property plus inheritance is unjust-but we put up with it because we are not convinced, at the moment, that anyone has invented a better system. The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.

But the tragedy is a fiction. Hardin’s essay — which is cited by far too many people who ought to know better — depended on the ideological conception of ‘nature’ and natural providence that the Royal Society’s neoneomalthusians are infected by.

One way we can tell that it is ideology and not fact at work is the same premises leading to opposite conclusions. For as surely as we can sense the necessity of the argument for the abolition of public property, as Hardin advances, we can sense its opposite. If nature must be protected through models of economic ownership, then why not abolish private property and regulate access to nature? If the injustice of feudal tyranny is no biggie, then why not the injustice of a communist tyranny, premised not on the basis of common ownership of the means of production, but on the basis of equal access to natural providence? After all, the Malthusian, like most environmentalists, believe that all value is produced by nature, not by man. That is what the Royal Society means when it says, ‘the destruction of nature is the backbone of the economy’. And they pay no more attention to scientific fact or history than Hardin did.

The emerging new feudalism coincides with the reign of a third King Charles, must as British feudalism’s (incomplete) abolition began with the end of the first. The gods and monsters that were abolished by science have been resuscitated by it. Power is being restored to a new clerisy that believes —flatters — itself that it is better connected to the (super-) natural forces that govern the elements than the hoi polloi, and so better placed to tell them how they must live than they are capable of deciding for themselves. As the old settlements fracture, they shore up the power of their institutions with myths and stories that owe nothing to the objectivity — nullius in verba — that characterised their contribution to the three centuries of the Age of Reason. And whereas in the past, these stories could travel no faster than a horse or pigeon, now they are beamed around the world in an instant.

History shows that there is no need to valorise nature in these fundamental or ‘intrinsic’ ways. And it shows that ‘nature’ is a contestable concept, which those who claim expert knowledge of its ‘intrinsic’ properties are found soon after to have been driven by ideology to fantasise about what it is. Yet it also shows how powerful these claims are. They have immense political utility. And that is why the Royal Society, the Royals, and the broadcaster, or any other institution of the state will admit no criticism, no debate, and no sense of history to their machinations. Environmentalism is the new state religion. It is, in fact, the state.

The fact that the Royal Society so confidently publishes these science-free ideological set-pieces speaks to the crises afflicting Britain’s institutions of all kinds. But confronting it as the establishment struggles to reassert its power means recognising that the problem is bigger than one that requires merely correcting a scientific error — a misconception about the role of a gas in the atmosphere that seemingly determines all history. We need also to recognise that the misconceptions that it seeks to assert as stone-cold object scientific fact are ideological, and exist within a historical situation. In the end, their project is a land-grab, a money-grab and a power-grab, the same as all feudalism before it.

Apologies for the recent silence. I have been trying to set up a number of new projects, and to find ways to fund them, which is not easy, despite claims about a Big Oil conspiracy — it mostly involves me doing other, ordinary paid work. This article is free, but most of the pieces here, especially new research, are behind a paywall. If you would like to help me and Climate Debate UK, please consider donating at the website, or taking out a paid subscription to this Substack.

Great essay, great research, shocking/disgusting Leftist garbage from the Royal Society. BUT PLEASE PLEASE learn to precis! Most people are busy, bombarded with equally shocking/disgusting news but the nation is DROWNING in news/videos/essays, we just haven't the time to watch/read it all. Only short, succinct and concise will have any impact. LESS IS MORE! And the BBC hasn't been around for a century yet.

Most interesting. And I will try to watch the RS/BBC video but I'm not promising anything.

I disagree with the term "eco-communist" though for the Royal Society's theologians. "Eco-feudalists" is much nearer.

Communists are by definition people who understand capitalism (or try to.) What's striking about the experts you quote is their complete detachment from historical and scientific data, as your article makes clear. Their "big argument" about intrinsic relationships ..with nature" and "senses of identity, sense of place, cultural relationships and rituals" is entirely subjective. At best , it's about aesthetics, but more likely an appeal to a cosy feeling of a nice picnic in the countryside.