The shocking figures on EV subsidies

New data on EV car sales show that in many places consumers are turning their noses up at battery-powered mobility. Campaigners point to healthy growth in some places. Are they right?

This week, The Telegraph published a story reporting that the sale of Electric Vehicles (EVs) have stalled or are falling in a number of European countries.

Whereas the EU and member governments cannot wait to abolish petrol and diesel cars (and indeed private transport, if one looks closely), many Europeans are choosing not to just make the full jump from fossil fuel-powered to battery-powered mobility.

The Telegraph’s graphic is quite compelling.

Many reasons have been hypothesised. The costs are still a significant obstacle to most ordinary people — those who on normal wages, and who put utility (or merely budget) before technological novelty. “Range anxiety” is the somewhat condescending term for people not taking at face value manufacturers’ hype about the performance of their products. Similarly, EVs can depreciate quite rapidly, with second hand buyers wary of the condition of batteries, despite which, however, there is not the market as there is for, for example, older EVs in the way there is for petrol and diesel cars.

All of these factors no doubt play a part. And to me assurances that EVs will ever be able to compete are for the birds for the simple reason that I forget to charge even my phone often enough. If I were even able to afford an EV, that is. I am not. I have always bought, or been given, older cars, a number of which I brought back from the dead — not something that is possible with lithium-ion batteries if you prefer to keep your hands and face attached to your body.

“Range anxiety?!”, scoff the EV fanboys, “The Polestar can do 300 miles on a single charge”. “Battery life?!”, laugh Musk’s minions, “The Tesla can do a million miles”.

Even if the claims were true, the Polestar will set you back between £44,950 and £63,950, and the Tesla £39,990 - £49,990. These sums are absurd to me.

Utility, which is a function of cost, is for most people the most decisive factor. And it seems even people with means are nonetheless rejecting EVs. Everybody knows that you will find a petrol station. But finding a charging point and the time are very different.

I was on a Talk TV debate this weekend, opposite climate journalist and campaigner, Donnachadh McCarthy.

Debates of this kind — ten minute slots on busy news shows — are extremely frustrating. Greens are given to machine-gunning factoids, cribbed from ersatz ‘civil society’ organisations’ and think tanks’ specious reports, nearly all of which are false, few of which they understand, at their opponents, and making many accusatory claims. And so one has to decide on-the-hoof which points, and how, to respond to the torrent in the very short time available. McCarthy wanted to talk about the Telegraph and its editor, Chris Evans, and to lump me in with them, to accuse me of being pro-oil, and against clean air, and what have you.

However, McCarthy did ultimately settle on one point, and that was the claim that despite the picture painted by the Telegraph article, EV sales were growing in a number of countries, and overall. The implication, not wholly unreasonable, but overstated in his broader argument, is that hostility to the green agenda drove the Telegraph’s emphasis on the bad news, rather than the growth.

I agreed with McCarthy. Indeed we should look at the countries where EV sales are growing, and find out why. And the problem I pointed out to him is that when we look, we discover that EV sales growth, for example in Britain, is driven not by consumer choice, but by government policy.

In general this is made clearest by the fact that increases in EV sales are driven by the fleet or commercial sector, not by private buyers. According to industry magazine, Fleet News, 14,991 EVs were sold in February this year, out of 84,886 total car sales, making that month the best for the new car market in 20 years, despite generally very depressed annual sales figures that have yet to show a recovery from Covid lockdowns. Fleet News adds that ‘Private car buyers have accounted for fewer than one in five (18.2%) new BEVs registered’. Assuming that these figures are consistent, that would mean that just 2,728 EVs were sold to private buyers in February. The remainder — 12,263 — were sold to fleets. Meanwhile, sales of petrol cars, at 48,000 were the same as the year before in percentage terms of 57% of the market.

The reason for fleets preferring EVs is obvious. But until recently, I’d not delved as deeply into these statistics as I have in other areas, such as wind power generation and economics. I knew, of course, that there exist subsidies for EVs. But the figures are much greater than you might think.

From 2011, the government’s Plug-in Car Grant (PiCG) gave £5,000 to EV buyers. In 2020, this was reduced to £3,000, and again to £2,500 in 2021. The grant scheme ended in June 2022, but support for EVs did not.

You can still get grants for electric wheelchair accessible vehicles (£2,500), motorcycles (£500), small (£2,500) and large (£5,000) vans, small (£16,000) and large (£25,000) trucks, and taxis (£6,000). But we are talking mainly here about cars.

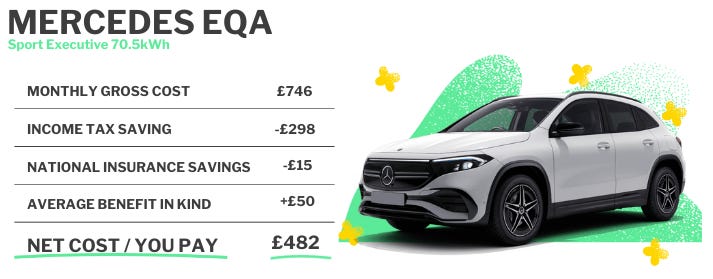

Rather than supporting EV buyers directly, the Government has created an extremely generous tax relief scheme for company cars. Here’s how that tax is calculated, as shown on a car sales website, using a relatively low estimate for the price of a new EV.

The Benefit in Kind (BiK) tax bands are based on the tailpipe CO2 emissions per mile, and are shown here. Since EVs are ‘zero emissions’, the Benefit in Kind of the company car (£20,000) is taxed at just 2% per year, which is multiplied by the buyer’s income tax bracket. By contrast, if your employer gives you a car worth £20,000, which produces 125-129 grams of CO2 per kilometre, the Benefit in Kind is taxed at 30% multiplied by your tax bracket (20%), you’ll be taxed at £1,200 a year.

Furthermore, employees who don’t necessarily require a company car are encouraged to lease though a scheme called ‘Salary Sacrifice’. This scheme allows people to save between 30 and 60% of the cost of leasing a car through their employers’ company, by ‘sacrificing’ the cost of leasing the car from a nominal salary. So, for example, if you earn £100,000 per year, and the cost of leasing a car is £10,000 per year, for tax purposes, your income is now £90,000 — you take slightly less home, but you pay less income tax, and your employer pays slightly less National Insurance Contributions. This is shown on the following graphic from a Salary Sacrifice scheme company.

If you wanted to buy a Mercedes EQA right out of the shop, it would cost you £50,000. But the Government’s subsidy schemes allows employees to have this luxury executive car delivered to your door, for £zero down, for just £482 per month — £5,784 per year.

If you’ve slightly more budget, the same firm offers a Mercedes EQS, which has a street prices of a whopping £110,000 for the bargain price to you of a tiny £755 per month.

But if the Benefit in kind was not rated according to the CO2 emissions of the car or the salary sacrifice scheme was not available, you would pay a great deal more. This is the point made by a Twitter user with the reliable moniker Obvious Fake Gorilla, who compared two similar cars, one being a full battery EV, the other a diesel hybrid, to produce a near £10,000 per year net difference.

By my brief experiments with leasing sites that do not use either subsidy scheme, a 4-year lease of the Mercedes EQS Salon would require a down payment of £20,230, plus four years of monthly payments at £2,248 (inc. VAT). The more modest EQA would require a down payment of £7,219, with four years of monthly payments at £802.

These are far bigger subsidies, albeit indirect, than the £3,000 grant scheme that was available until 2022, though the schemes overlapped.

But the subsidies do not end there.

The government will use taxpayer’s money to pay for the installation of charging points at a work place, up to “75% of the cost of the work, up to a maximum of £15,000”, including “up to £350 per chargepoint socket installed”, and “up to £500 per parking space enabled with supporting infrastructure”.

EVs are not subject to Vehicle Excise Duty — ‘road tax’ — amounting to an annual saving of £190.

And EVs are exempt from traffic-reduction schemes, such as London’s Congestion Charge — worth £15 per day.

So let us imagine a use-case… an executive at a company in Central London who lives in the commuter town of Gerrards Cross. He caught the end of the PiCG — £3,000. He saves £10,000 per year leasing a Mercedes EQE. The company received £850 grant to install his charging point, from which the company pays 0% VAT on the power. He drives into Central London five days a week for 45 weeks a year, saving £3,450 on the Congestion Charge. The benefits to him are thus £17,300 in the first year, £13,450 in subsequent years. (I have not included the VAT-free power in this calculation.)

This is why there is growth in the EV market, and why it is confined to fleet cars. The subsidies and incentives are extraordinary.

It's all punishment for the poor and reward for the rich.

But some of the very richest people in Britain believe that the taxpayer is not burdened enough. The House of Lords report on EVs earlier this year recommended to the government that they should:

Tackle the disparity in upfront costs between electric and petrol and diesel cars, by introducing targeted grants to support consumers buying affordable models.

What is this word ‘affordable’? What does it mean? When did it enter the English language?

Who would buy an ‘unaffordable’ car?

The affordable car is, in general, a car that runs on diesel or petrol. EVs are more expensive because they are more expensive. Taking money from taxpayers to give grants to people does not make EVs more ‘affordable’. Hence, the benefits of grants and subsidies and other carrot-and-stick policies accrue to the wealthy and middle classes, not to people on lower incomes, for whom EVs will never be affordable, but who will be hit by the anti-car policies that dominate local and national governments’ agendas.

Despite the empty talk of making EVs ‘affordable, I believe that what is happening here is a terrible undermining of the freedoms we took for granted, with practically no public discussion about the consequences of limiting mobility.

When I was quite young, at some point in the 1990s, before I could drive, I had been unemployed for a few months after being made redundant. On one day, I was offered two interviews, one in the north, and one in the midlands — both quite far from my home in the southeast. My only means of getting to them was by train. The price of the ticket was greater than the unemployment benefit — I don’t recall which — I would get for that fortnight, and I didn’t qualify for subsidised tickets. Because I was able, I took the gamble, and was offered both jobs.

But what if I had not been able? What if I did not have some modest savings or a family? What if that allowance was necessary for my day-to-day living? I passed my test and got a car shortly after. The petrol for the journey back to my home cost just a small fraction of the price of the train ticket. Had I had the car and licence earlier, the risk of the gamble would be far smaller. By restricting mobility, and by making everything more expensive, we limit the opportunities that everybody, but especially younger people have — and those are people whose access to private transport is limited by rising costs of living.

The car was once more than merely a symbol of freedom to young people. It was freedom. By putting obstacles in the way of their natural sense of adventure, we dampen their initiative. A toxic culture is brewing.

Compare that story of a hypothetical young person on their first steps with the fact of the taxpayer subsidising the wealthy business owner’s daily commute.

Some might say in reply that perhaps unemployed people ought to be given free train tickets to travel to interviews. But that remains only the smallest part of the story. What about the move itself — stuffing belongings into a hatchback with the seats folded. What about the trips to Ikea, to furnish the new place? What about the trips back home to see friends and family? As the costs mount, so utility and liberty are sacrificed for environmental ideology. Subsidies patch merely the superficial aspects of the injustices that are created by the green lust to transform society, whether society wants it or not.

Criticism of Net Zero, the climate agenda and environmentalism is not merely criticism of the ridiculous policies and grotesque wealth transfers. Greens want to change culture and the way people see their world, and they are not concerned with what anyone else might think about those transformations. Vast amounts of money are at stake. And that’s why the likes of McCarthy fib endlessly, and why EV sales mandates have faced practically zero scrutiny. The government has simply bought opinion, in exactly the way it did when it offered people free money to put solar panels on their roofs. There is no part of the climate agenda which does not require such wealth transfers. Not solar panels. Not heat pumps. Not wind farms. And not EVs.

Thanks Ben. You have laid bare the green mobility welfare state which is paid for indirectly by the tax on everyone else’s energy bills. Sadly the scam is set to continue with our myopic politicians who have seen no huge bill for eco indulgences they didn’t want to sign off.

McCarthy is absolutely typical of your Green Zombie. His remarks are a machine gun diatribe of utter nonsense which nearly always start with your paid by the fossil fuel industry hoping to avoid any meaningful debate. Your research aligns with my anecdotal analysis.... I know a lot of people with EVs but every single one is a company car. They are taking a massive tax break (compared to ICE cars) which is why they drive them. The poor are paying for the middle class virtue signallers. Your wider point about the impacts of losing out on mobility is very interesting - the catastrophisers of course won't bother.